NLP Paper Club Week1 (Sep 25 - Oct 1)

Published:

In this blog post I tried to introduce top papers in ML (particularly in NLP) and give a brief overview on them.

Paper #1: Effective Long-Context Scaling of Foundation Models

Motivation

The motivation behind this paper stems from the need to develop and enhance language models capable of handling significantly longer contexts. The authors introduce a series of long-context Large Language Models (LLMs) designed to process context windows of up to 32,768 tokens effectively.

Contributions

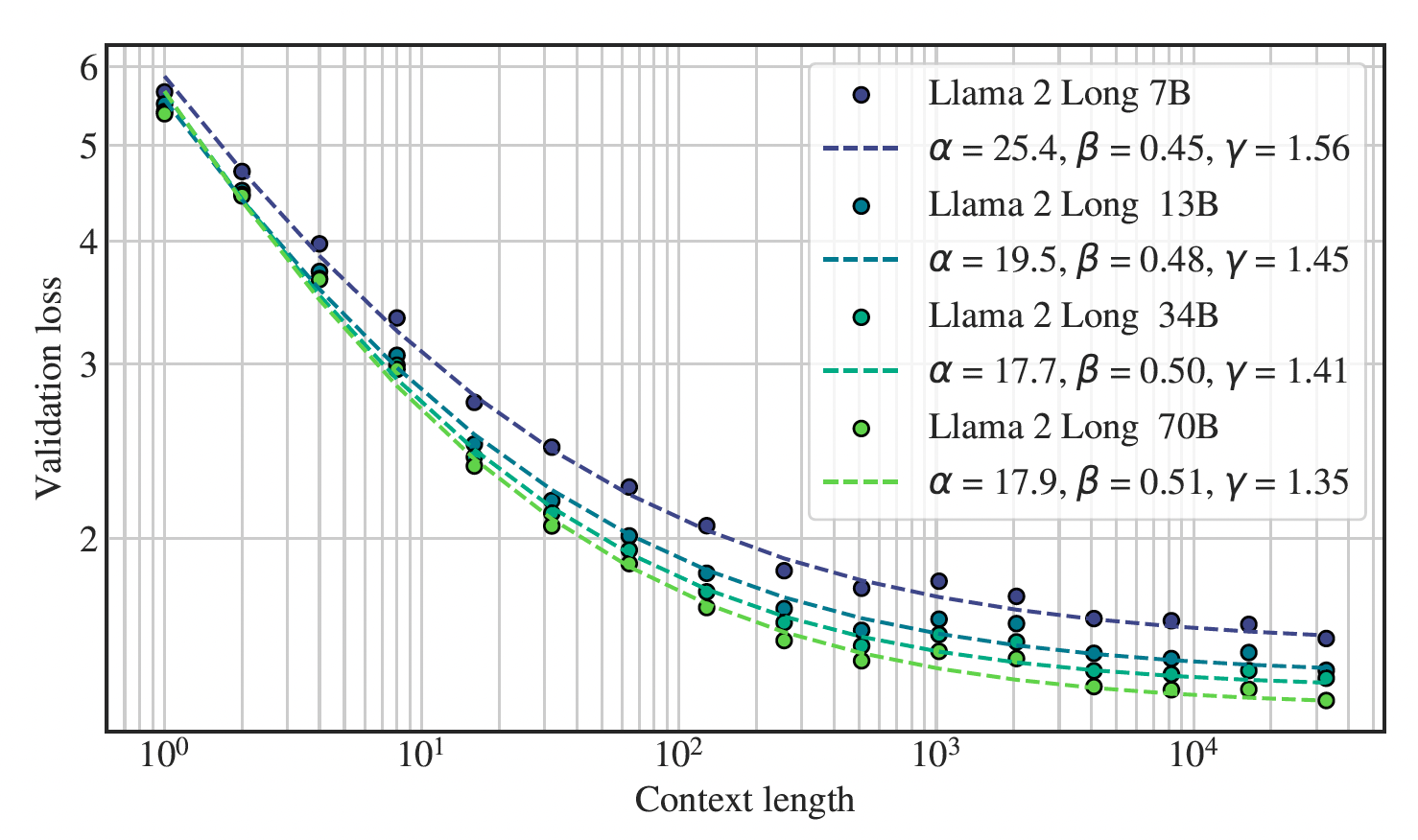

The paper presents a significant contribution in two aspects. Firstly, it reveals a robust power-law scaling pattern in language models, emphasizing the importance of extended context for Large Language Models (LLMs). This scaling behavior enhances the ability of LLMs to effectively utilize more extensive contexts. Secondly, when compared to LLAMA 2 on research benchmarks, the models exhibit substantial improvements in long-context tasks and modest enhancements in standard short-context tasks, particularly in coding, math, and knowledge benchmarks. Furthermore, the paper introduces a cost-effective procedure for instruction finetuning in continually pretrained long models without any human-annotated data, resulting in a chat model that outperforms gpt-3.5-turbo-16k on various long-context benchmarks, including question answering, summarization, and multi-document aggregation tasks.

Methodology

Continual Pre-training

Training with longer sequences can lead to substantial computational overhead, primarily attributable to the quadratic nature of attention calculations. In attention mechanisms, as the sequence length expands, the number of calculations increases quadratically. Therefore, the motivation of continual pre-training is to learn long-context capabilities by continually pre-training a short-context model. To do so, The authors keep the original Llama 2 architecture intact or continual pre-training and only make a necessary modification to the positional encoding. Considering that sparse attention reduces computation time and the memory requirements of the attention mechanism by computing a limited selection of similarity scores from a sequence rather than all possible pairs, the authors choose not to use sparse attention. The reason behind this is that given the dimension of Llama 2 70B model ($h = 8192$) the cost of attention matrix calculation becomes a computational bottleneck when only the sequence length exceeds $49,152 (6h)$ tokens.

Positional Encoding

In early 7B-scale experiments, a limitation discovered in LLAMA 2’s positional encoding (PE) that prevents the aggregation of information from distant tokens. To address this, a minimal but essential modification to the RoPE positional encoding (Su et al., 2022) has been made by reducing the rotation angle (controlled by the “base frequency b”). This adjustment minimizes RoPE’s decaying effect on distant tokens, enhancing long-context modeling.

Data Mix

In addition to the modified PE model, various pretrain data mixing strategies have been investigated to enhance long-context capabilities. This involved adjusting the ratio of LLAMA 2’s pretraining data or introducing new, longer text data. the findings underscore the significance of data quality over text length in the context of long-context continual pretraining.

Optimization Details

Then, LLAMA 2 checkpoints continually pretrained with progressively longer sequence lengths while maintaining the same token batch size as in LLAMA 2. The training process encompasses a total of 400B tokens distributed over 100,000 steps. By employing FLASHATTENTION , they managed to keep GPU memory overhead at a negligible level, even when extending the sequence length. Specifically, they observe only around a 17% decrease in speed when transitioning from a sequence length of 4,096 to 16,384 for the 70B model.

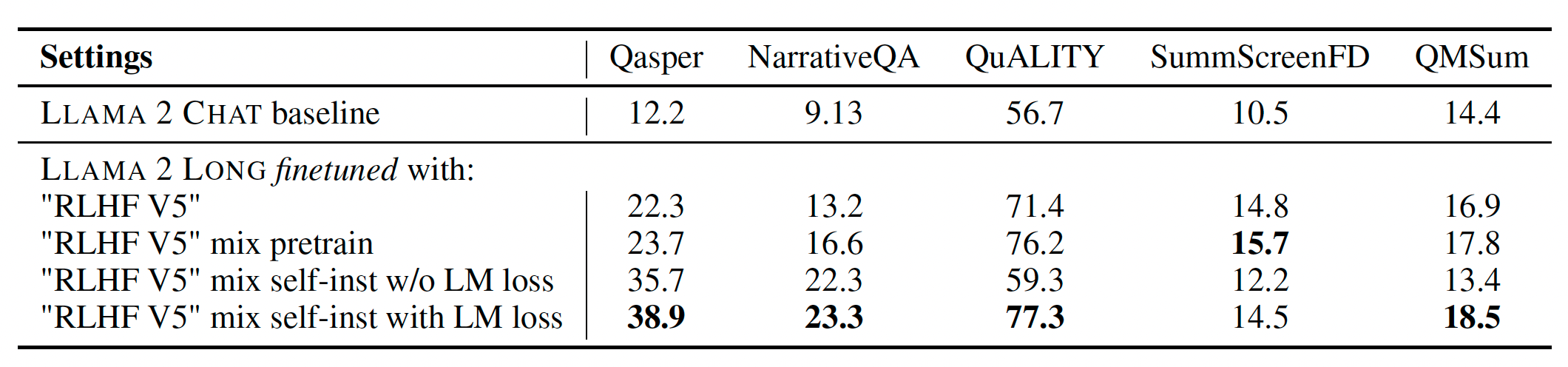

Instruction Tuning

Gathering human demonstrations and preference labels for LLM alignment is a costly and challenging task, especially in long-context situations involving intricate information and specialized knowledge. To solve this challenge, the authors proposed a straightforward approach involving augmentation of the RLHF dataset used in LLAMA 2 CHAT with synthetic self-instructed long data generated by LLAMA 2 CHAT itself. The data generation focuses on Q-A task and involves different steps:

- First starting from a long pre-training corpus, a random chunk of this corpus is chosen.

- Then Llama 2 Chat is prompted to write question-answer pairs based on information in the text chunk.

- Then both long and short form answers with different prompts are collected.

- Finally, the Llama 2 again is prompted to verify the model-generated answers. Given a generated QA pairs, the original long document (truncated to fit the model’s maximum length) is used as the context to construct a training instance. To make it more clear, they fine-tune the model with short instruction data from Llama 2 CHAT (RLHF V5) and then blend it with some data from pre-training (avoid forgetting of previous long context), and self-instruct data.

Paper #2: Graph Neural Prompting with Large Language Models

Motivation

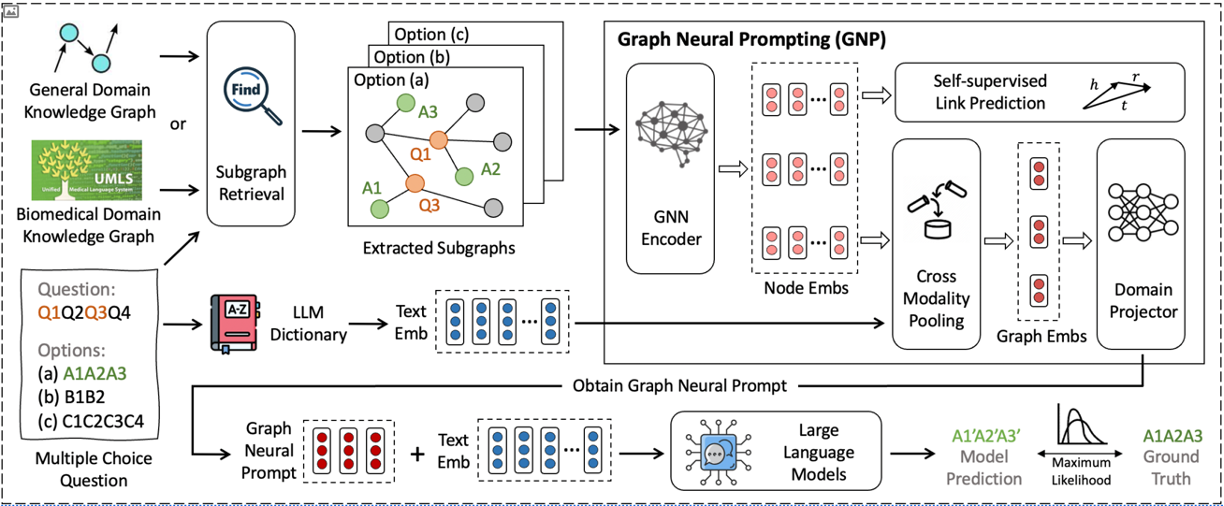

Despite the success of Large Language Models (LLMs) in handling different real-world applications and availablity of aligning these LLMs to different downstream tasks, they have been denounced for memorizing facts and knowledge (capturing and returning knowledge properly). Knowledge Graphs (KGs), on the other hand, offer a structured and systematic approach to knowledge representation. As a result exsisting methods have emerged, aiming to combine KGs and textual data during the pre-training of LLMs. Nevertheless, integrating KGs and text during pre-training can be challenging due to the extensive parameters LLMs contain. Therefore one primary motivation here is to employ pre-existing pre-trained LLMs. A straightforward approach would be to feed KG triples directly into LLMs. However, KGs often contain extraneous contextual information that can mislead LLMs. This issue gives rise to another significant motivation for this work: to identify beneficial knowledge from KGs and integrate them into pre-trained LLMs.To address these challenges, authors propose Graph Neural Prompting (GNP) a novel plug-and-play method to assist LLMs in learning beneficial knowledge from KGs.

Contributions

In this paper, the authors introduce GNP as a method to learn and extract the most valuable knowledge from KGs to enrich pre-trained LLMs. The key contribution of this work is its ability to improve baseline LLM performance by 13.5% when the LLM is kept frozen. In addition, the proposed method contains various tailored designs, including a standard GNN, a cross-modality pooling module, a domain projector, and a self-supervised graph learning objective.

Methodology

It needs to be mentioned that the assumed task is multiple choice questions answering.

Prompting LLMs for Question Answering

Prompting is the defacto approach to elicit respones from LLMs. To create prompts for multiple choice question answering given questions $Q$, the optional context $C$, and the answer options $A$:

- First tokenize the concatenation of $C$, $Q$, $A$ into a sequence of text tokens $X$.

- Then designs a series of prompt tokens &P&

- Finally Prepend &p& to &X& tokens which will be the input to the LLM. The LLM model can be trained with an objective of maximum likelihood of cross-entropy loss: \(\mathcal{L}_{llm} = - \log p(y|X, \Theta)\)

where $\Theta$ refers to the parameters of the model.

Subgraph Retrieval

To align the input text tokens $X$ with the massive knowledge graph $G$, we retrieve subgraph of $G^ \prime$ containing relevant entities to the tokens in $X$. In this stage the retrieval happens based on two-hop neighbors.

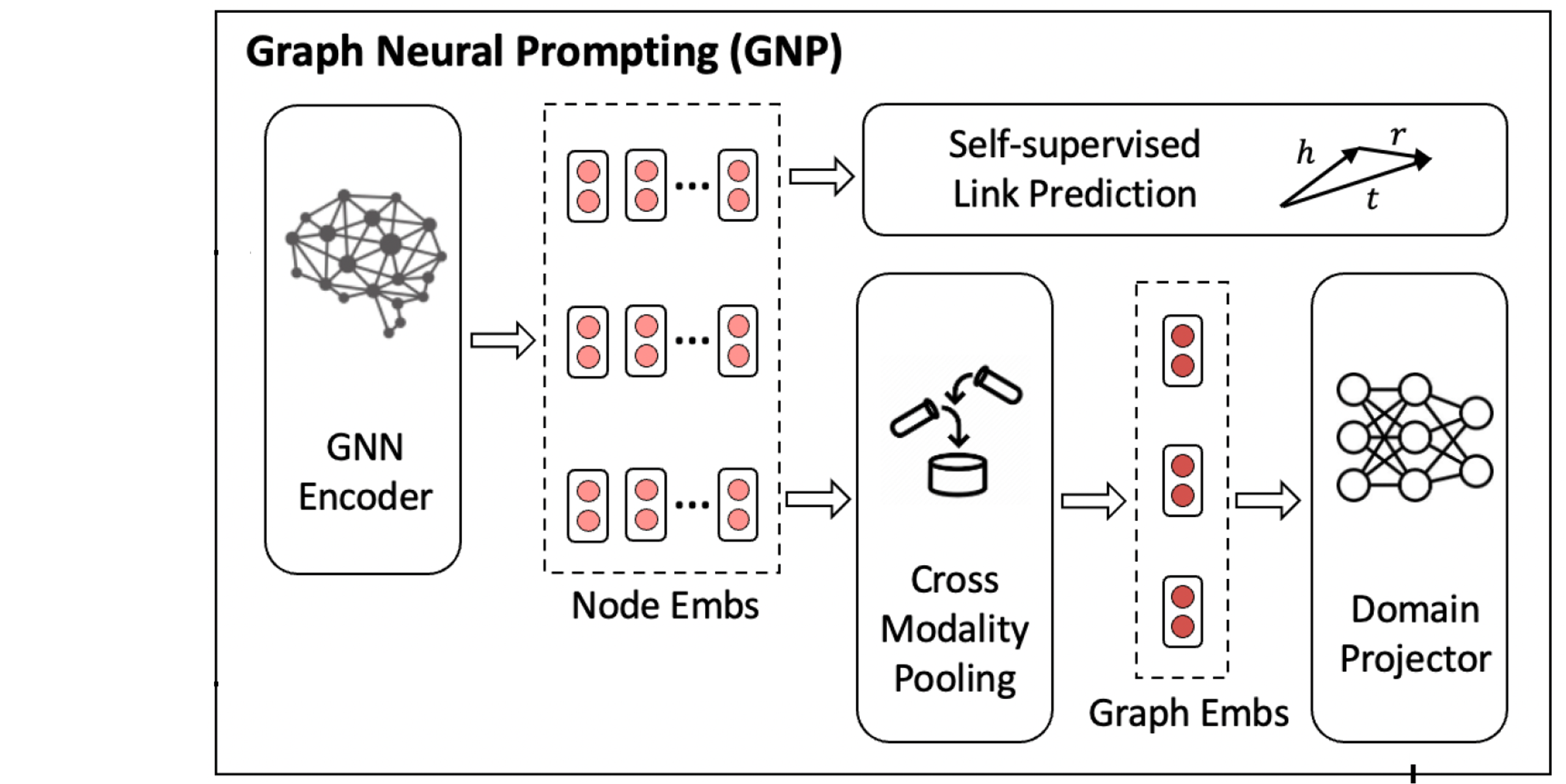

Graph Neural Prompting

Graph Neural Prompting is composed of four different modules:

- GNN Encoder

- Cross-modality Pooling Module

- Domain Projector

- Self-supervised Link Prediction

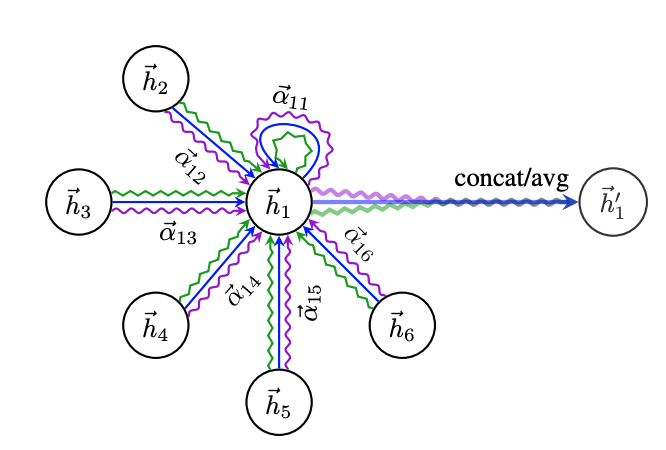

GNN Encoder

To avoid knowledge noises, we employ a graph neural network (GNN) to encode the knowledge inside the subgraph $G^ \prime$. To do so, first we initialize the node embeddings using pre-trained entity embeddings (from prior works on entity embeddings) and then a standard graph attention network (GAT) is employed as our GNN to encode the most relevant entities and their complex relationships.

The encoding process is formulated as follows:

\[H_1 = \mathcal{f}_{GNN}(G^ \prime)\]Where $H_1$ represents the node embeddings learned by GNN.

Cross-modality Pooling

The main objective of this module is to identify the most relevant entities of encoded subgraph based on the prompt ontext (input tokens $X$). This identification occurs through a series of distinct stages.

In the initial step, a self-attention layer is employed on the node embeddings ($H_1$), yielding:

\[H_2 = Self-Attn(H_1)\]In this equation, $H_2$ represents the node embeddings subsequent to the application of self-attention.

The second step involves transformation of the embedding of input tokens ($X$) into the space of node embeddings $H_2$, achieved through the following operation:

\[\mathcal{T^ \prime} = FFN_1(\sigma(FFN_2(\mathcal{T})))\]Here, $\mathcal{T}^ \prime$ signifies the embedding of input tokens within the dimensional space of node embeddings, and $\mathcal{T}$ denotes the initial representation of input tokens. The $\sigma$ idenotes the GELU activation function, and $FFN_1$ and $FFN_2$ correspond to feed-forward networks.

Subsequently, cross-modality attention is computed using $H_2$ as the query and $\mathcal{T}^ \prime$ as the key and value:

\[H_3 = softmax[H_2.(\mathcal{T^ \prime})^T / \sqrt(d_g)].\mathcal{T^ \prime}\]In the above formula, $H_3$ represents the final node embeddings, achieved through the utilization of cross-modality attention.

a graph-level embedding is generated by performing average pooling on the node embeddings ($H_3$):

\[H_4 = POOL(H_3)\]Domain Projector

To establish a robust mapping between the graph-level embedding and the input text embedding, a domain projector is employed. This projector serves the crucial purpose of bridging the inherent disparities between graph-level node embeddings and input text embeddings, facilitating their seamless integration. In essence, the projector transforms the graph-level embeddings into the same dimension as the input text embeddings ($d_t$).

This transformation is achieved through the following operation:

\[Z = FFN_3(\sigma(FFN_4(H_4)))\]Here, $Z$ denotes the Graph Neural Prompt, and $FFN_3$ and $FFN_4$ are feed-forwar neural networks. The Domain Projection process acts as a pivotal link, ensuring that graph-level embeddings are seamlessly integrated into the input text embedding space, thereby enhancing the model’s overall understanding and performance.

Self-supervised Link Prediction

While the cross-entropy objective enables the model to learn and adapt to the target dataset, a link prediction task is introduced to further refine the model’s understanding of relationships between entities. This task involves masking out a set of edges ($\varepsilon_{mask}$) within the subgraph $G^{\prime}$. Given the node embeddings of both the head entity and the tail entity in a triplet, denoted as ${h_i, t_i} \in H_3$, a method called DistMult is utilized to map these embeddings into vectors, specifically $h, r, t$. A score function, $\phi(h_i, t_i) = \langle h, t, r \rangle$, is defined to generate scores for each triplet. A higher $\phi$ value indicates a higher likelihood that ${h, t, r}$ represents a correct positive triple rather than an incorrect negative triple.

In this context, the model is tasked with predicting the masked edges ($\varepsilon_{mask}$) as positives while treating other randomly selected edges as negatives. The link prediction loss is formally defined as follows:

\[\mathcal{L}_{lp} = \sum_{(h_i, r, t_i) \in \varepsilon_{mask}}^{} (\mathcal{S}_{pos} + \mathcal{S}_{neg})\]The final objective funtion $\mathcal{L}$ is defined as the weighted combination of $\mathcal{L}${llm} and $\mathcal{L}${lp}:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathcal{L}_{llm} + \lambda \mathcal{L}_{lp}\]Incorporating self-supervised link prediction enhances the model’s grasp of entity relationships, contributing to a more refined and comprehensive understanding of the data.

Strong Points of the paper

- This approach demonstrates a substantial performance improvement, with a +13.5% enhancement in the baseline when the LLM is kept frozen.

- The GNP method presents a novel solution for effectively filtering out noise from knowledge graphs and integrating the valuable insights they contain into the prompt.

Weak Points of the Paper

- This approach is only applied on multiple choice question answering task.

- The choice of Falcon-T5 as the underlying LLM is not accompanied by a clear rationale. Several other LLMs, like Llama 2, could be viable alternatives for these tasks.

- The paper lacks an in-depth exploration of the complexities involved in both training and inference processes, particularly with regard to the time requirements. A more comprehensive discussion of these aspects would provide valuable insights into the method’s practical feasibility.

Paper #3: ADAPTING LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS VIA READING COMPREHENSION

Motivation

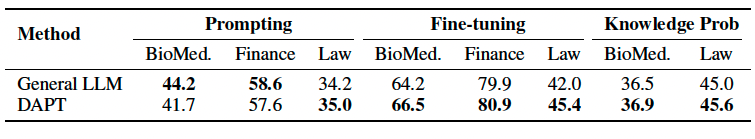

The paper investigates whether continued pre-training on domain-specific raw corpora benefits large language models. The authors find that continued training on domain-specific raw corpora can endow the model with domain knowledge, but drastically hurts its prompting ability. To address this issue, they propose a simple recipe which automatically converts large-scale raw corpora into reading comprehension texts, to effectively learn the domain knowledge while concurrently preserving prompting performance. Their experiments show the effectiveness of their method in consistently improving model performance in three different domains: biomedicine, finance, and law.

Contributions

As illustrated in Table 1, when the language model has undergone continued pre-training on the domain-specific raw corpora, the performance on prompting drastically decreases. Therefore, the authors found a way to improve the performance of LLMs on domain-specific tasks without sacrificing their prompting ability. This is a significant contribution, as it opens up new possibilities for using LLMs in a wider range of applications. Here is a brief summary of the contributions of the paper:

- Investigated continued pre-training for large language models (LLMs) and found that it can endow LLMs with domain knowledge, but hurts their prompting ability.

- Proposed a simple recipe for converting large-scale raw corpora into reading comprehension texts, which allows LLMs to effectively learn domain knowledge while preserving prompting performance.

- Demonstrated the effectiveness of their method in consistently improving model performance on various domain-specific tasks in three different domains: biomedicine, finance, and law.

Methodology

Instead of continuing to train the language models on domain-specific raw corpora, the authors propose a two-stage training process:

- (1) Reading phase: train the model on raw text.

- (2) Comprehension phase: train the model on comprehension task where each raw text is followed by a series of tasks (in format of Q-A) related to its content in this stage.

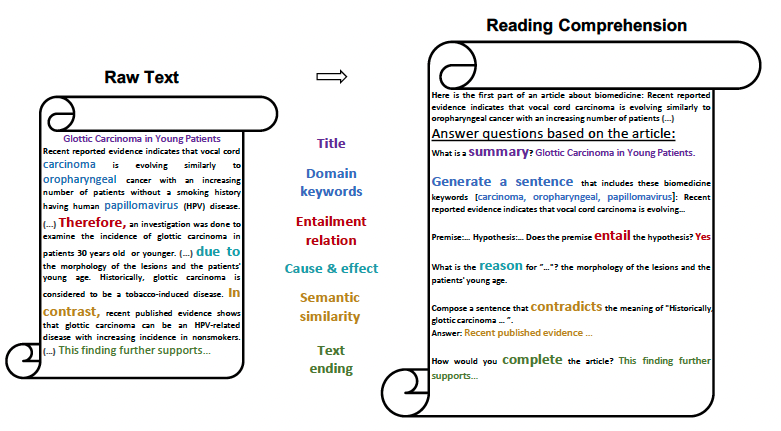

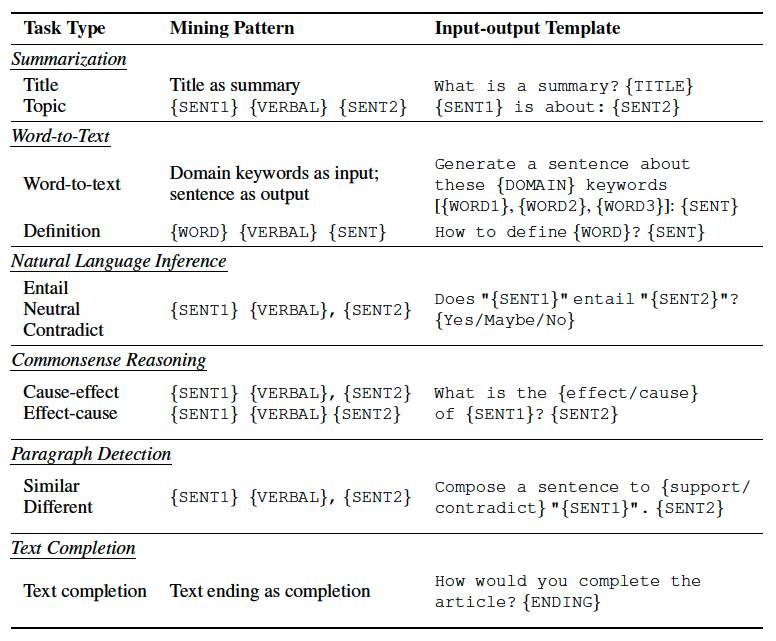

Creating Reading Comprehension Texts

This paper is inspired by the idea of mining tasks from raw pre-training corpora to enhance zero-shot capability, which was introduced by van de Kar et al.. This approach extract tasks from raw text through a handful regex-based patterns. Similarly, authors focus on leveraging the self-supervised nature of this mining strategy to create comprehension tasks. In other words, this approach involves appending the pre-training raw text corpora with some mined tasks such as Summerization, Word-to-text, Natural language inference, Commonsense reasoning, Paragraph detection, and Text completion from the same raw text. As illustrated in the Figure 6, the comprehension task data starts with the body of raw text followed by a phrase like “answer questions based on the article:”. Afterwards, the input-output pairs of each individual task are added to the text.

To create the Summerization task, the model is prompted with the query “what is a summary?” and the title of the text is considered as the ground truth. Another way to create the summarization task is using regex-based patterns, where we look for sentences that follow the pre-defined pattern of “{sentence1} talks about/is about/’s topic is {sentence2}”.

To create Natural Language Inference task, another regex-based pattern (illustrated in Table 2) is used to search for “premise-hypothesis-relation” triplets within the raw text. For instance, they classify relationships as “Entailment” if linked by “Therefore” and “Neutral” if linked by “Furthermore”.

For Commonsense Reasoning that assesses physical and scientific reasoning while incorporating common sense, they detecti cause-and-effect logic in sentences through regex patterns (Table 2). To create tasks, input-output pairs are formulated, such as “What is the reason of {SENT1}? {SENT2}.”

To gather the data for Paraphrase Detection regex patterns from Table 2 are used to search for sentence1-sentence2-label triplets. However, it is found that these patterns do not consistently identify sentences with strictly equivalent meanings. For instance, sentences connected by words like “Similarly” may not have similar meanings. Therefore, they convert the classification task into a generation task, asking the model to create a sentence either supporting or contradicting the given sentence, “Can you create a sentence that contradicts the meaning of {SENT1}? {SENT2}” when the label is “Different”.

For Text Completion data, queries like “How would you complete the article?” are inserted between sentences to stimulate the model. The benefit of this task is its flexibility, as it doesn’t rely on specific mining patterns and can be applied to any raw text.

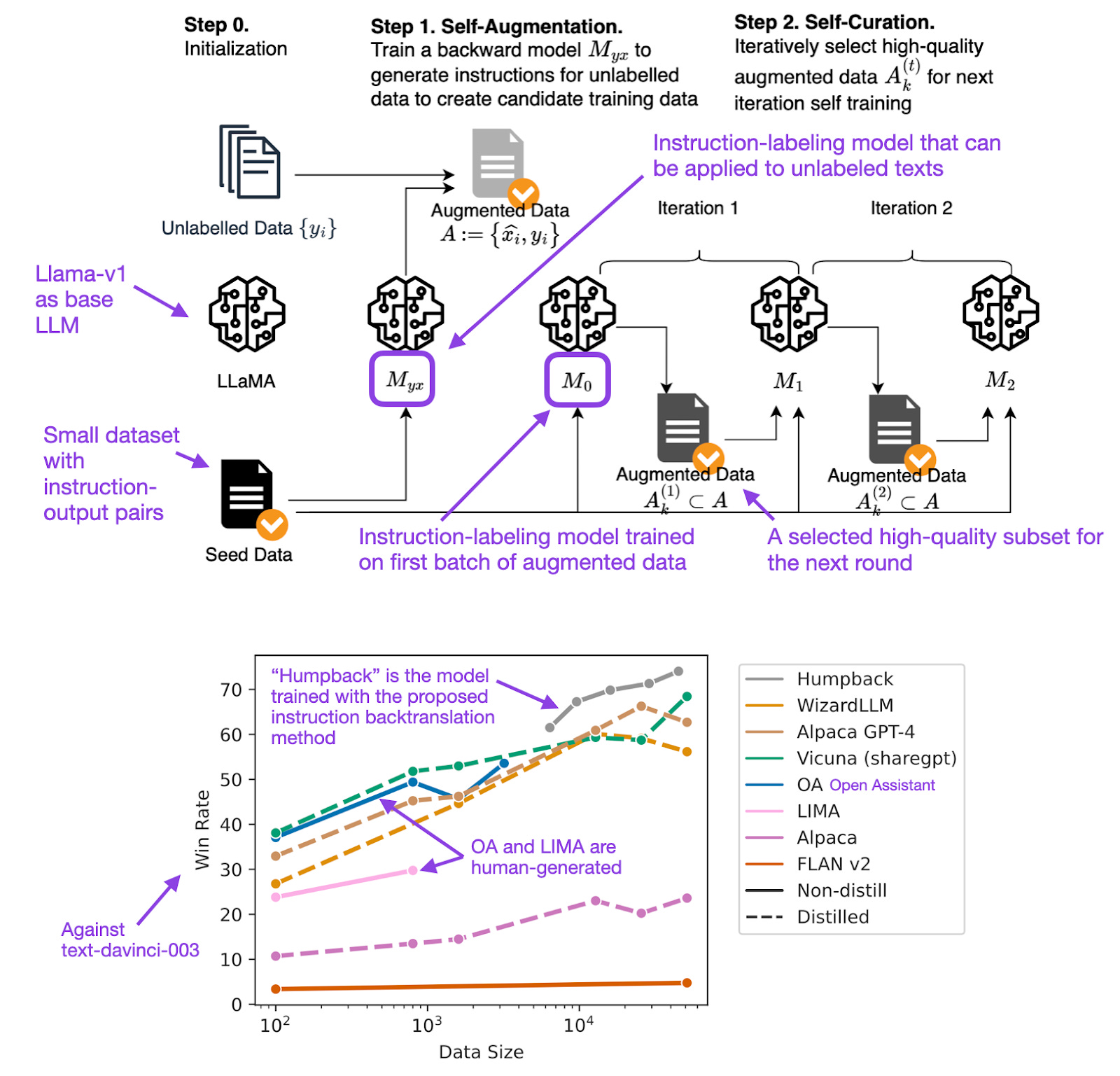

Paper #4: Self-Alignment with Instruction Backtranslation

Motivation

This paper presents a novel approach, instruction backtranslation, as an efficient alternative to traditional methods for improving large language model (LLM) performance in instruction following. By fine-tuning a pre-trained LLM with instructions generated from unannotated text sources, instruction backtranslation outperforms both manual dataset collection and distillation in various instruction following tasks.