Prompt Engineering Guide

Published:

Prompt Engineering

Prompt engineering is a discipline focused on crafting efficient prompts for large language models (LLMs). These skills aid in comprehending LLM capabilities and limitations. Researchers apply prompt engineering to enhance LLM performance in various tasks, from QA to arithmetic reasoning. Developers use it to create compelling interfaces for LLMs and other tools.

Beyond prompt design, prompt engineering encompasses a spectrum of skills essential for LLM interaction and development. Prompt engineering is a crucial competency for understanding and enhancing LLM capabilities, improving safety, and incorporating domain knowledge and external tools.

This guide compiles the latest papers, and models for prompt engineering to meet the growing interest in LLM development. In this blog post, I delve into the art of prompt engineering for LLMs, exploring a variety of strategies and techniques to craft effective prompts that harness the full potential of these robust AI systems. Whether you are a developer, researcher, or enthusiast, this resource will empower you to create prompts that yield insightful and contextually relevant responses.

In this guide, we divide the prompts into two distinct settings:

This division helps us explore specialized techniques and best practices for each type of prompt construction, ensuring that you have a comprehensive understanding of how to effectively engineer prompts for both scenarios.

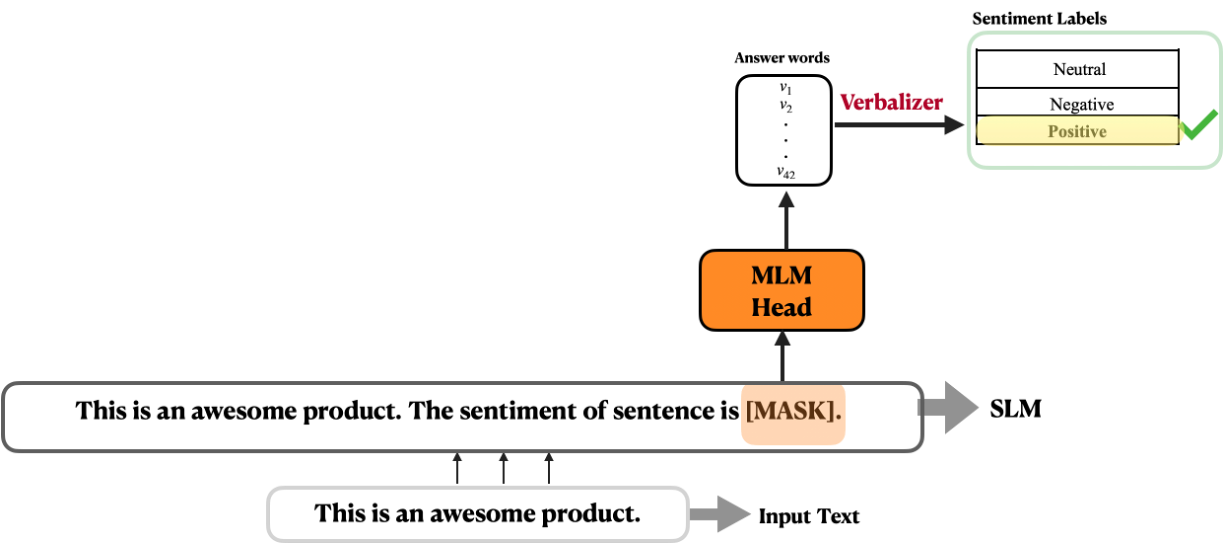

Fill-in Slot Prompts for Prompt-based Learning

In contrast to traditional supervised learning, which trains a model to take an input $x$ and predict an output $y$ as $P(y|x)$, prompt-based learning relies on language models that directly model the probability of text1. In this paradigm, a textual prompt template with unfilled slots is applied to an input sentence $x$, transforming the downstream task into a Masked Language Modeling (MLM) problem. This reformulation empowers the language model to statistically fill in the unfilled slots, which can be considered as the predicted label $y$ for the specific task. For instance the prompt template $T$ for a sentiment classification task can be defined as follow:

T = x. The sentiment of the sentence is [MASK].

where $x$ indicates the original input sentence.

In case of having an input sentence $x$ = That is an awesome product., applying the prompt template $T$ on the input sentence $x$, we will have the prompted input sentence $x^ \prime$ as:

x´ = That is an awesome product. The sentiment of the sentence is [MASK].

Given the prompted input sentnece $x ^\prime$, the language model will fill the unfilled mask token [MASK], which will be translated into one of the actual labels $y$ by a verbalizer (See Figure 1).

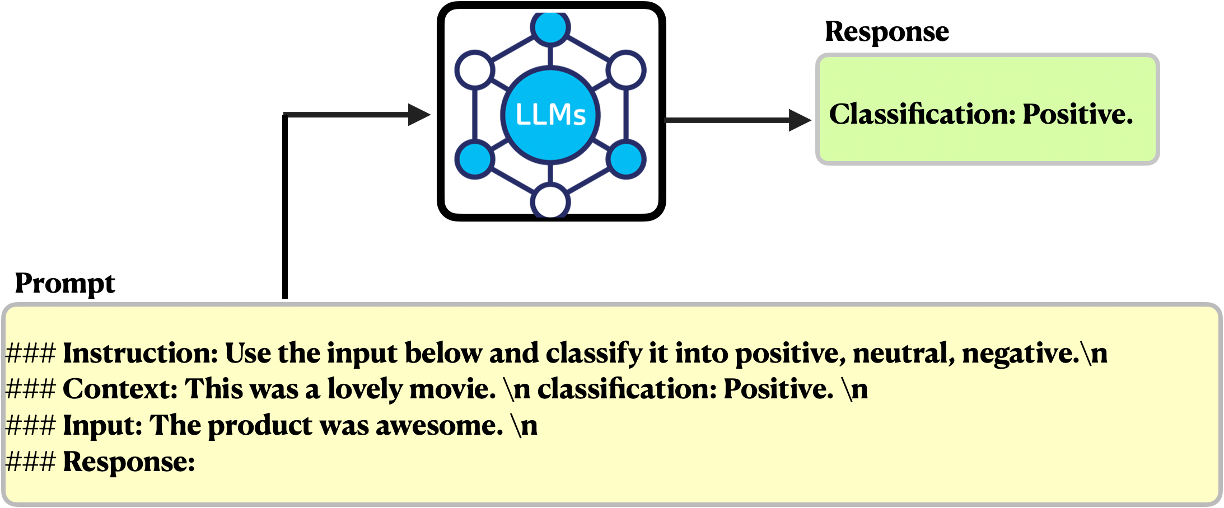

Prompts for Generative Large Language Models

LLMs, such as GPT-32 and Llama 23, are usually very good at generating grammatically correct and semantically meaningful text. However, despite their outstanding performance, they can produce false information, bias, and toxic text outside the user’s requirements. One approach to address this issue is to prompt LLMs with task-specific instructions and/or solved examples, helping them learn patterns and perform a range of NLP tasks based on the user’s expectations. In this setting a prompt can contain the following elements (See Figure 2):

- Instruction: Clearly defines the specific task the LLM should perform.

- Context: Offers additional context, including solved examples or supplementary information, to guide the model towards more contextually relevant responses.

- Input Data: Specifies the input data on which the task is to be performed.

- Output Indicator: Articulates the desired format for the model’s output.

It is important to note that while these elements can significantly enhance prompt effectiveness, they are not mandatory. Users have the flexibility to design and customize prompts according to their specific requirements and preferences.

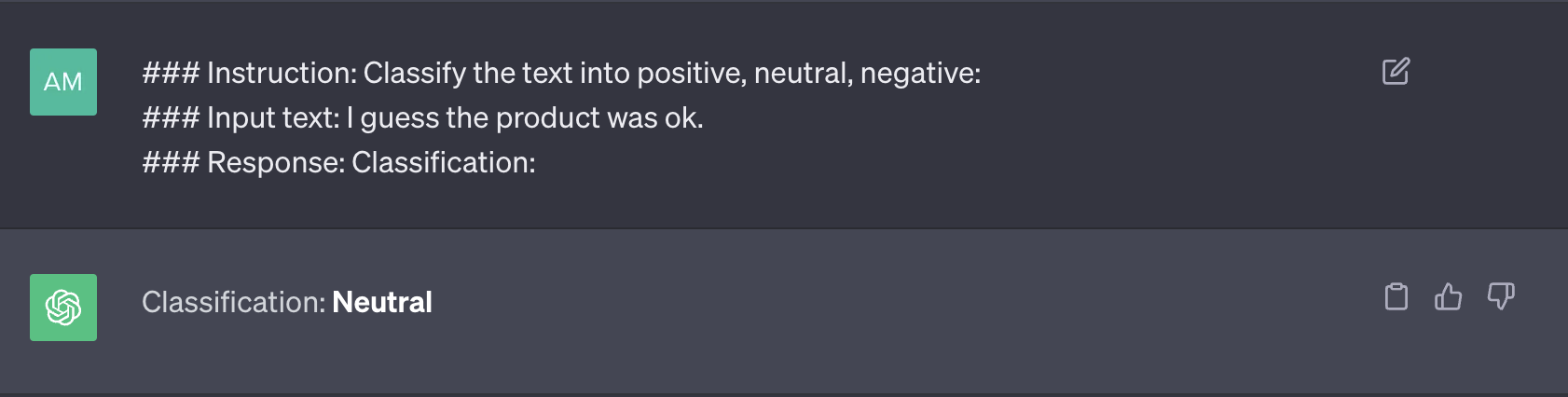

Zero-Shot Prompting

As mentioned earlier, LLMs, trained on extensive data and finely tuned to follow instructions, can perform tasks with zero-shot ability. Zero-shot prompting involves providing a prompt that is not part of the training data to the model, yet the model can generate a result that the user desires. This promising technique further enhances the utility of LLMs for a wide range of tasks. Here is one example for zero-shot prompting:

As illustrated in Figure 3, the prompt lacks a solved example, which characterizes this prompting approach as zero-shot prompting.

Few-Shot Prompting (In-Context Learning)

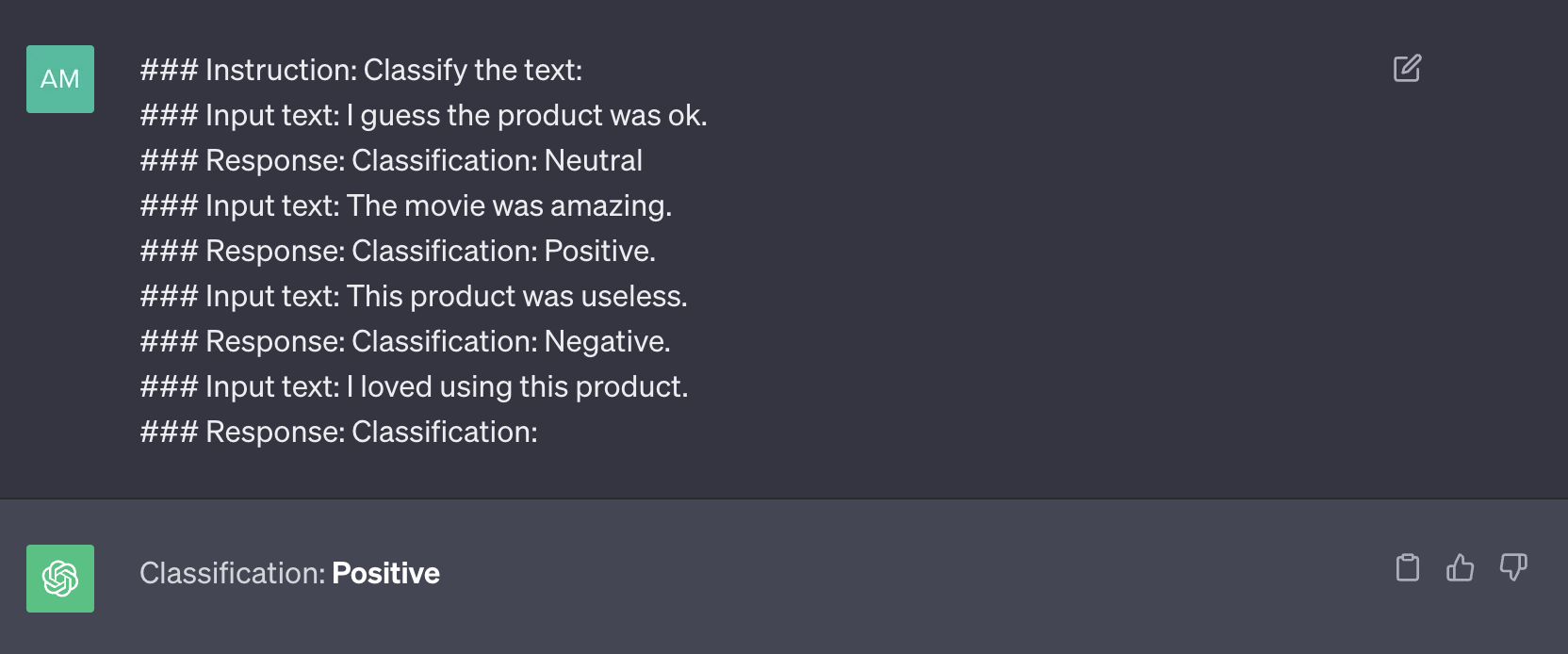

While LLMs already demonstrate impressive zero-shot capabilities, they still face challenges with more complex tasks in a zero-shot setting. To address this challenge, Few-shot prompting, or In-Context Learning (ICL), is introduced. ICL represents a distinct approach to prompt engineering, where task demonstrations are integrated into the prompt in natural language format. Through ICL, the capability of LLMs is leveraged to handle novel tasks without requiring fine-tuning. Furthermore, ICL offers the versatility to be combined with fine-tuning, unlocking even greater potential for more dynamic and robust LLMs. Here is one example for ICL:

As illusterated in Figure 4, there are some solved examples involved in the prompt to improve the response of LLM. This approach is called few-shot prompting which is also known as in-context learning.

Manual Discrete Prompt Engineering

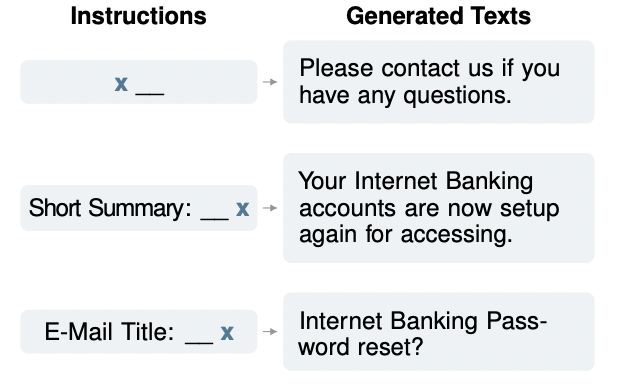

Manual construction based on human introspection is the most straightforward approach to creating a discrete (hard) prompt. In this context, a discrete prompt refers to one made up of individual tokens in natural language form. Prior work in this field includes the LAMA dataset4, which offers manually generated fill-in prompts for knowledge evaluation in language models. Additionally, Schick and Schütze5 6 7 utilize pre-defined prompts in a few-shot learning framework for tasks such as text classification and conditional text generation (See Figure 5 taken from Schick and Schütze6).

Automatic Prompt Engineering

Creating manual prompts may seem intuitive and offer some task-solving capabilities, but it has some challenges:

- Crafting and experimenting with these prompts can be time-consuming and requires expertise, especially for complex tasks like semantic parsing.

- Existing discrete prompt-based models, such as LAMA4 have shown that a single word change in prompts can cause an extreme difference in the results.

- Even with experienced prompt designers we may not end up with finding the most optimal prompt. In light of these challenges, various methods have been introduced to automate prompt construction. These methods can be categorized into:

- Automatic discrete (hard) prompt engineering

- Automatic continous (soft) prompt engineering

In the following sections, we delve into the specifics of each category and explore the various proposed methods.

Automatic Discrete Prompt Engineering

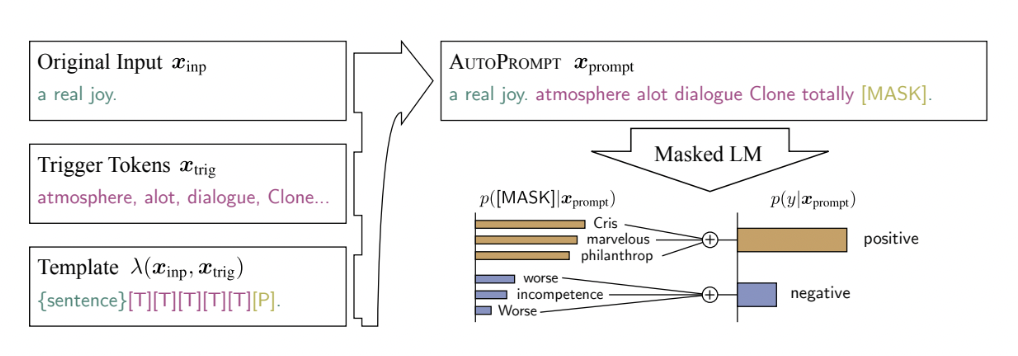

AutoPrompt is an approach to automatically create the fill-in prompts for different NLP tasks based on the gradient search. They first add a number of trigger tokens shared across all prompts (denoted by [T] in Figure 6). These trigger tokens initialized as [MASK] tokens and then iteratively updated to maximize the label likelihood. At each step, they compute a first-order approximation of the change in the log-likelihood that would be produced by swapping the $j$th trigger token with another token in the language model vocabulary. Finally, after $k$ forward pass of the model, they select the top-$k$ tokens as candidates.

Image source: AutoPrompt

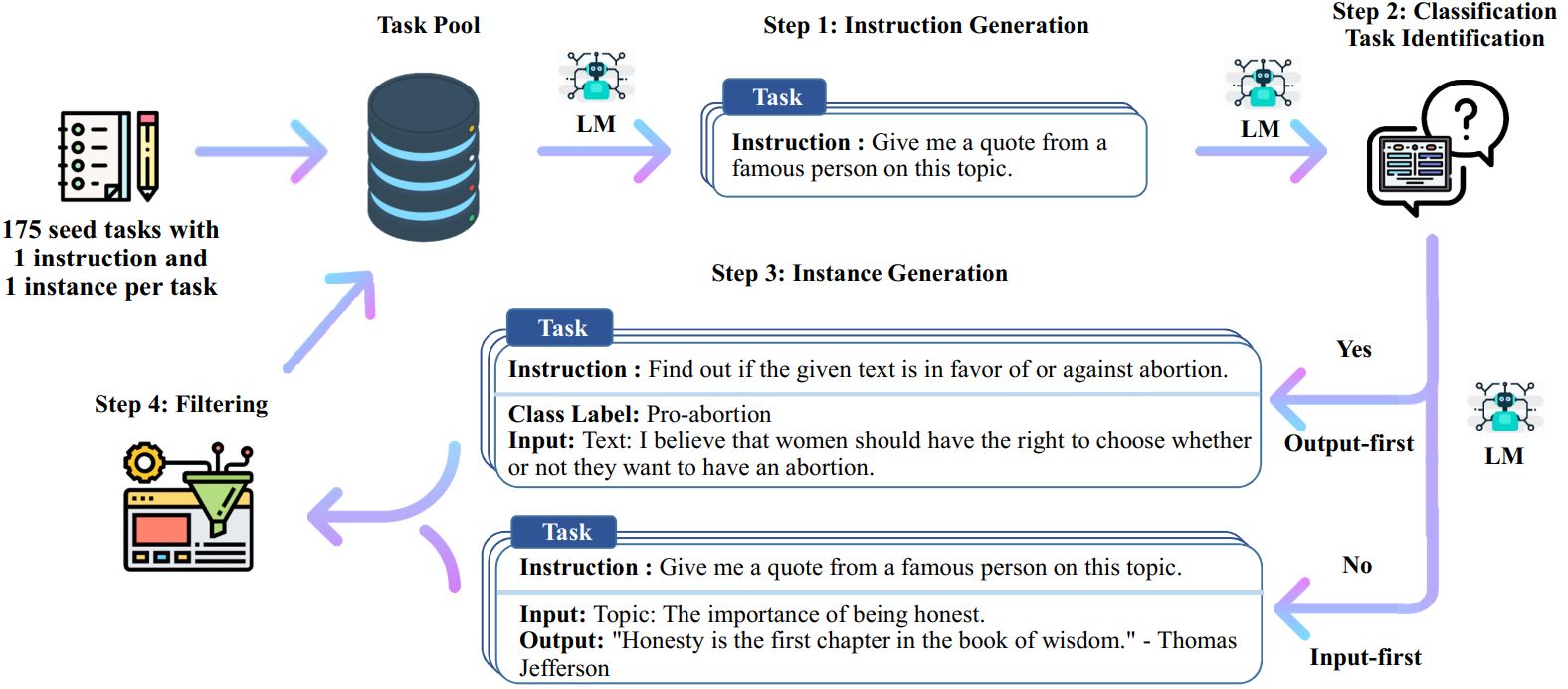

Self-instruct is another framework proposed for automatic generation of optimal instructions that helps language models improve their ability to follow natural language instructions. The process of self-instruct is an iterative bootstrapping algorithm that starts with a seed set of instructions that manually written by humans. These manually written instructions are used to generate new instructions with input-output pairs. Afterwards, the generated instructions are filetered out to remove low-quality or similar ones. The result of the self-instruct is a large collection of instructional data for different tasks and can be used to fine-tune LLMs on these different tasks (See Figure 7).

Image source: Self-instruct

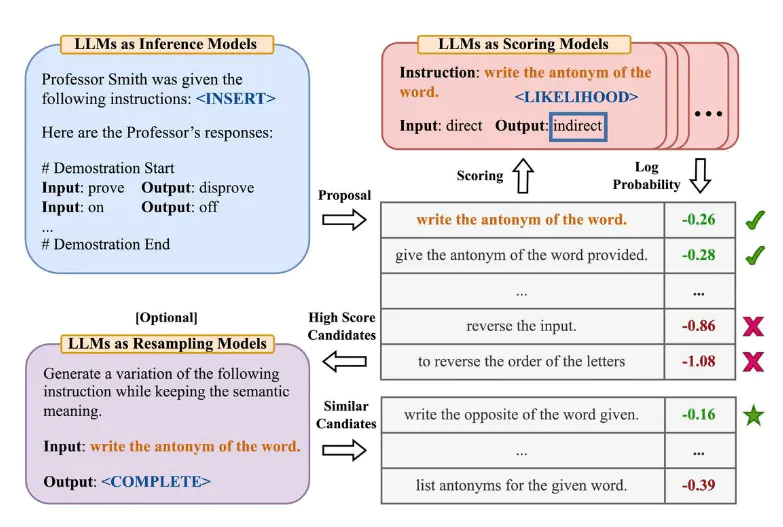

Zhou et al. proposed an Automatic Prompt Engineer (APE) framework for automatic instruction generation and selection. This approach reformulates the instruction generation as natural language synthesis considered as a black box optimization problem using LLMs to generate and score them to choose candidate solutions. In the first step, this framework employs an LLM (as an inference model) that is given a set of input-output pairs to generate instruction candidates. Afterwards, another LLM (target model) is used to produce the log-likelihood of each generated instruction as its corresponding score. Finally, the most appropriate instruction is selected based on the scores (See Figure 8). The main contribution of this paper is to automatically optimizing the prompts that results in a more optimal chain-of-thought prompt “Let’s work this out in a step by step way to be sure we have the right answer.” improving performance on the MultiArith and GSM8K benchmarks.

Image source: APE

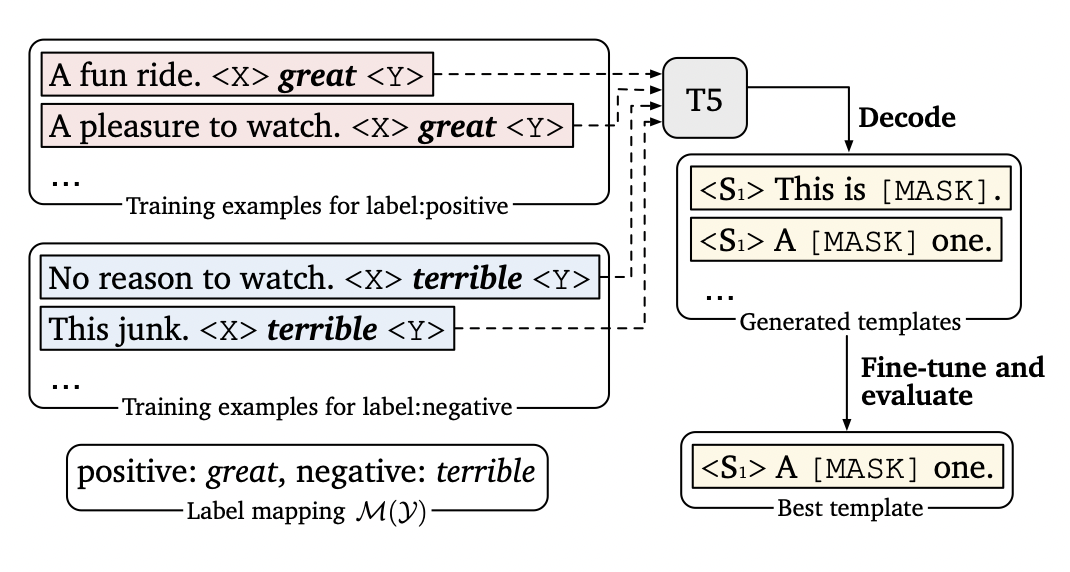

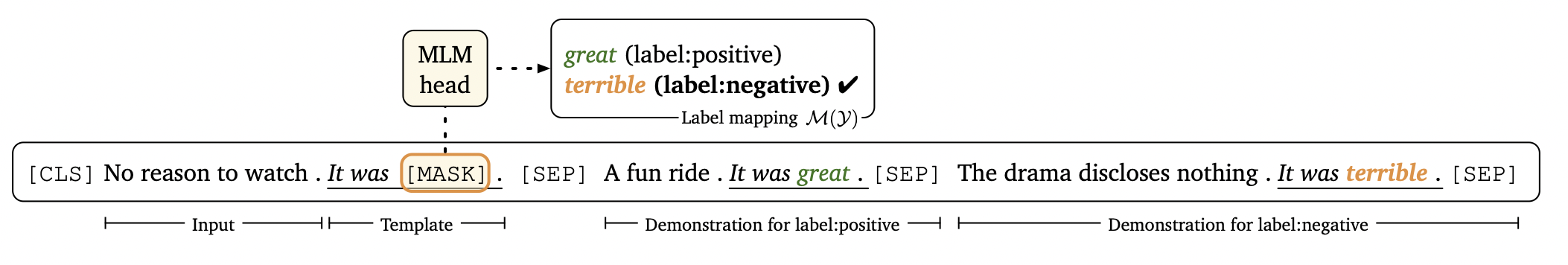

LM-BFF, a framework for fine-tuning language models with a focus on few-shot NLP tasks, introduces a novel pipeline for generating fill-in prompts. This dynamic generation process incorporates demonstrations into each prompt. In the illustration presented in Figure 9, the framework leverages the T5 language model to create prompt candidates using input sentences from the training dataset, combined with their corresponding label words. Beam search is employed to select a wide array of decoded prompts. Subsequently, each generated prompt is fine-tuned on the training dataset, and the evaluation dataset is utilized to identify the most suitable prompt with the best performance.

Upon selecting the optimal generated fill-in prompt, the second stage is influenced by in-context learning. In this phase, similar examples for each label are sampled from the training dataset. When we mention similar examples, we are referring to sentences that are semantically close to the input sentence (embedding similarity is obtained using SBERT). These semantically related sentences are concatenated with their labels (as demonstrations) to the input sentence, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Image source: LM-BFF

Image source: LM-BFF

Incorporate Knowledge into Promopt

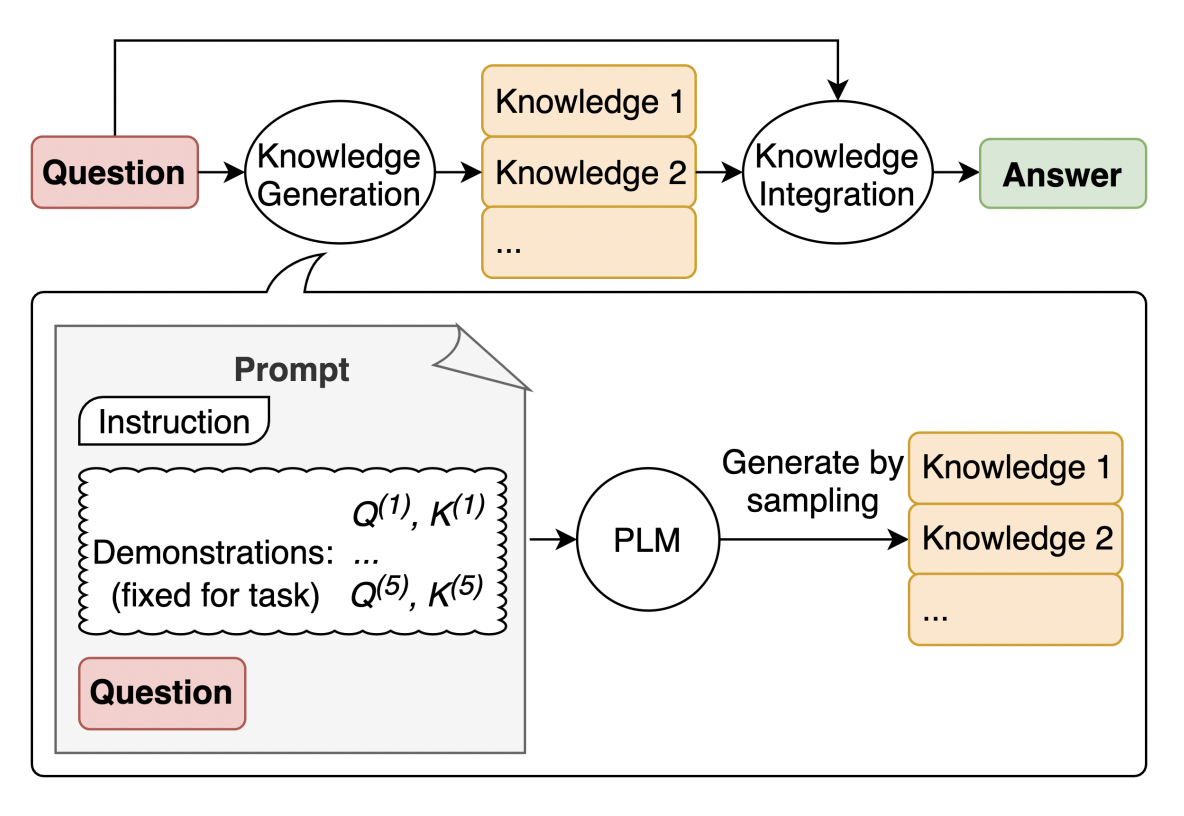

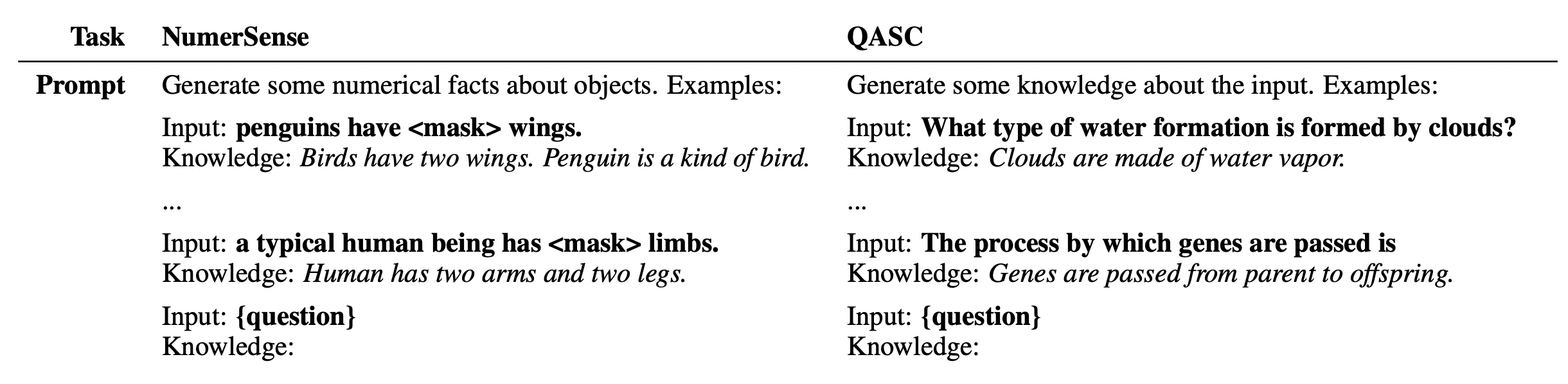

Another method for automatically generating optimal prompts incorporates knowledge within the prompt, which enhances the language model’s predictive accuracy. In this context, Liu et al. introduced the generated knowledge prompting method, which comprises two key phases:

Knowledge Generation: A language model generates knowledge statements based on the given question: \(P(K_q|q)\)

Knowledge Integration: The generated knowledge statement is assimilated into the question (prompt) and presented to the language model as an inference model to predict the answer (Refer to Figure 11). This process is represented as follows: \(a ^\prime = \argmax P(a|q, K_{q})\)

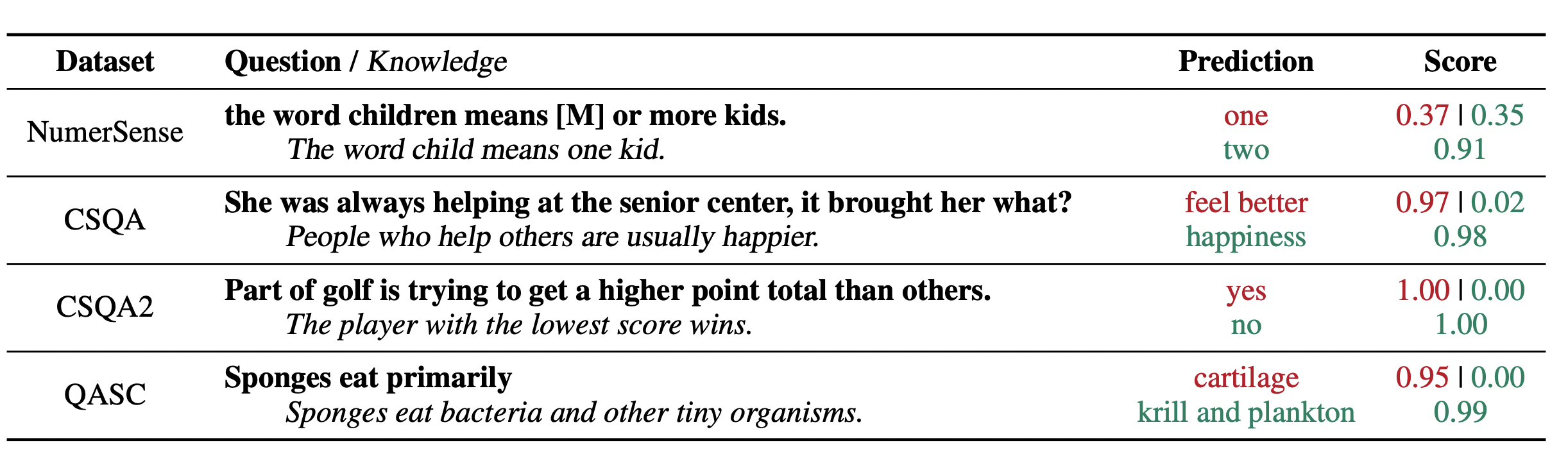

Here, $q$ represents the question, $K_{q}$ signifies the corresponding knowledge statement, and $a^ \prime$ denotes the predicted answer. Table 1 illustrates examples of knowledge statement generation, while Table 2 showcases the answers generated by LLMs in two different settings: one with knowledge statements incorporated and another without (For more examples, please refer to this post).

Image source: Liu et al.

Tables source: Liu et al.

Reinforcement Learning for Prompt Generation

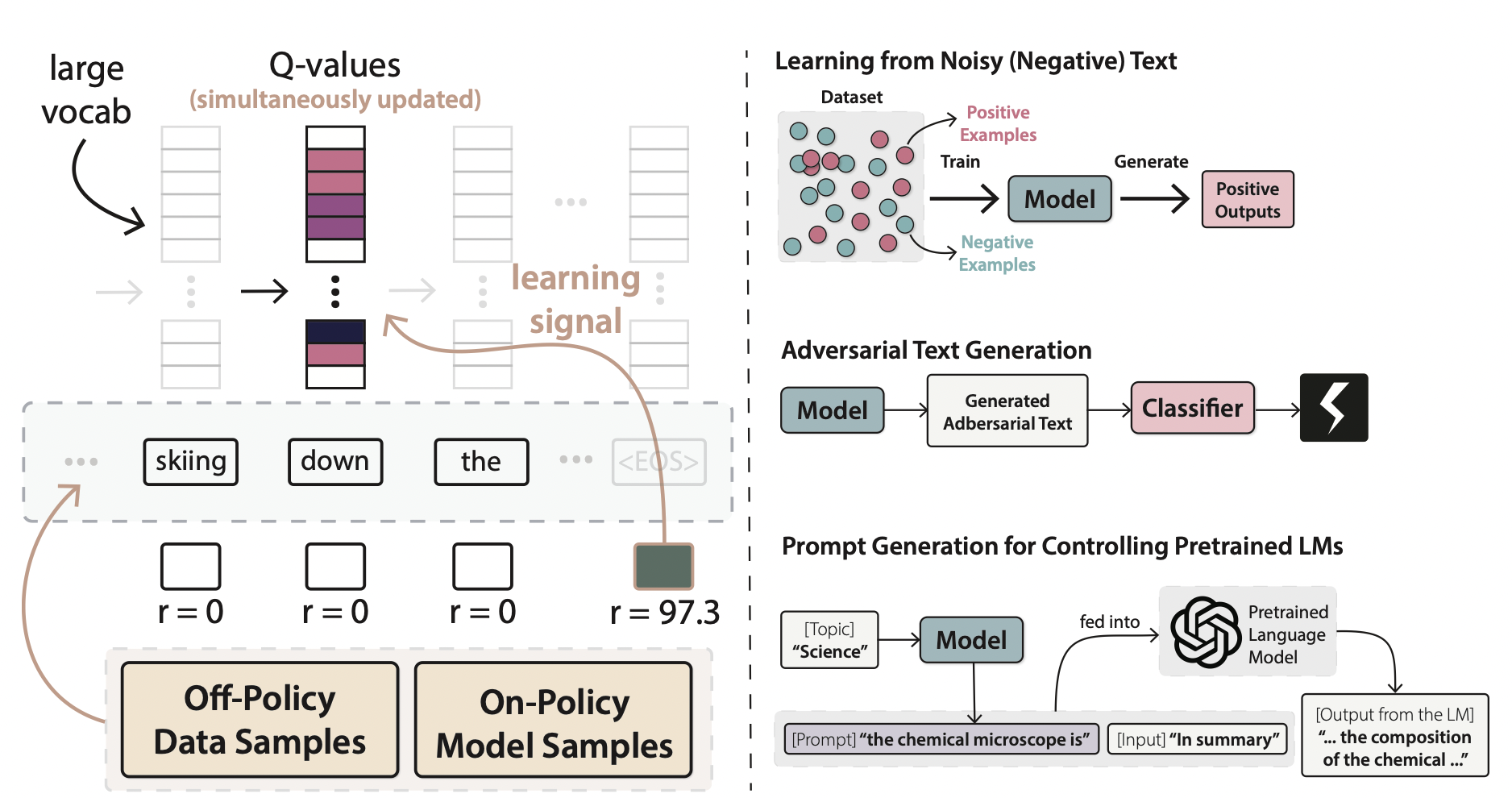

Guo et al. presented a novel RL approach to text generation, viewed through the lens of soft Q-learning (SQL). In Figure 12, the process of employing Q-learning for text generation is depicted.

Image source: Guo et al.

Automatic Continuous Prompt Engineering

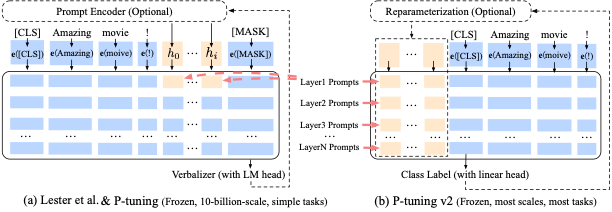

Previous research has highlighted the challenge of discovering suitable discrete prompts in natural language. An approach that is insensitive to the variations in discrete prompts could be beneficial. An alternative strategy involves employing continuous (soft) prompts, where continuous tokens are incorporated into the input and continually updated instead of using discrete tokens. In contrast to hard prompts, soft prompt tuning concatenates the embeddings of the input tokens with a trainable tensor that can be optimized via backpropagation to enhance modeling performance on a target task. In this context, Lester et al. introduced Prompt Tuning, a parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) approach for refining LLMs. Within this framework, continuous prompts are integrated into the input embedding sequence. A lightweight neural network, positioned before the frozen LLM, tunes the soft prompt tokens during training. This strategy not only facilitates the learning of the most effective task-specific prompts but also diminishes the volume of parameters subject to updates during training, thanks to the frozen status of the LLM (See Figure 13).

Image source: P-tuning V2

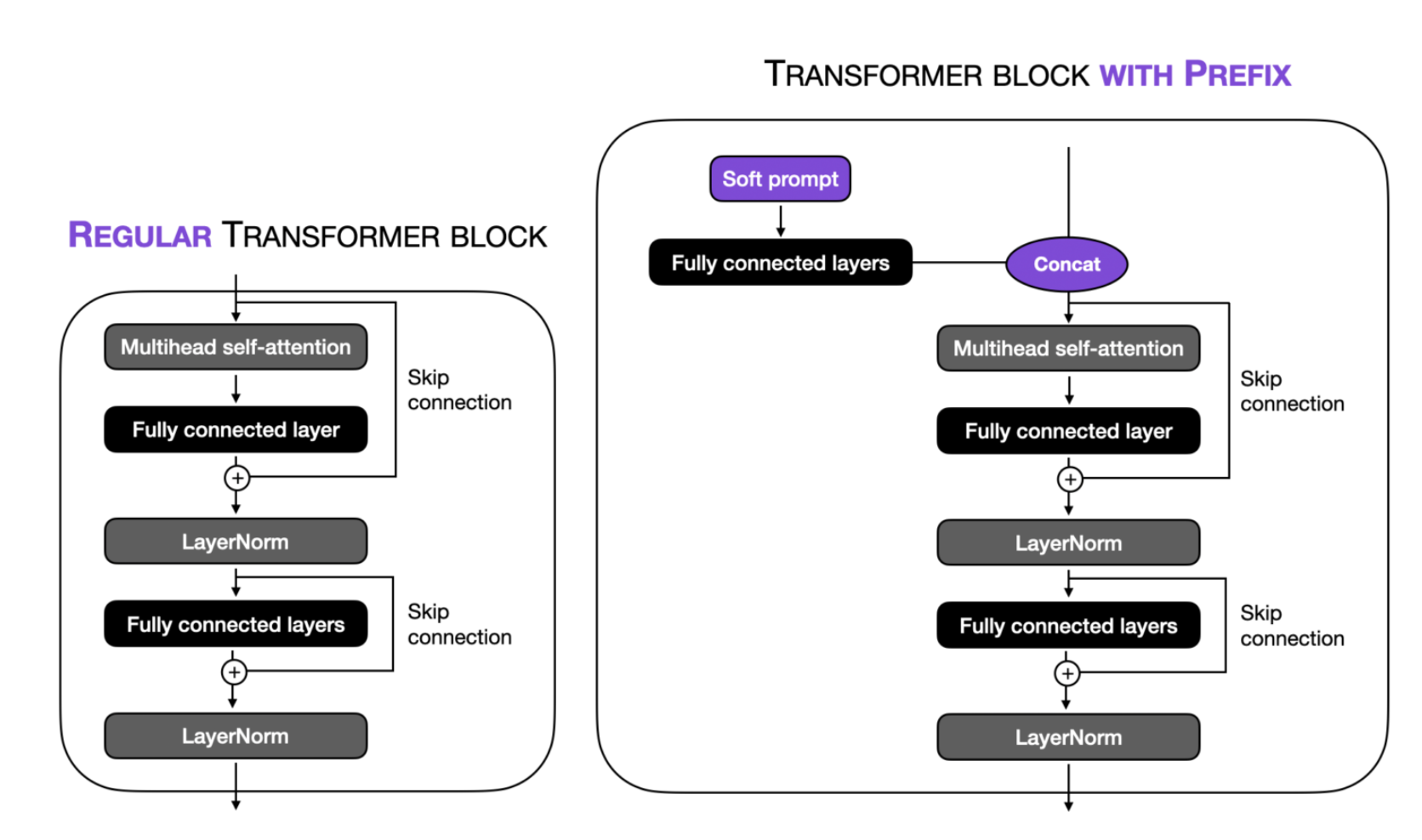

A distinct variant of prompt tuning is Prefix-Tuning. In Prefix-tuning, the idea is to include trainable tensors in every transformer block, instead of input embeddings as in prompt tuning. Moreover, Prefix-tuning incorporates a fully connected layer (a compact multilayer perceptron with two layers and a nonlinear activation function in between) into every transformer block to attain the most effective soft prompts (Refer to Figure 14).

Image source: Lightning AI

It is essential to note that prefix tuning, due to its modification of the model’s layers, necessitates fine-tuning a more significant number of parameters when compared to prompt tuning.

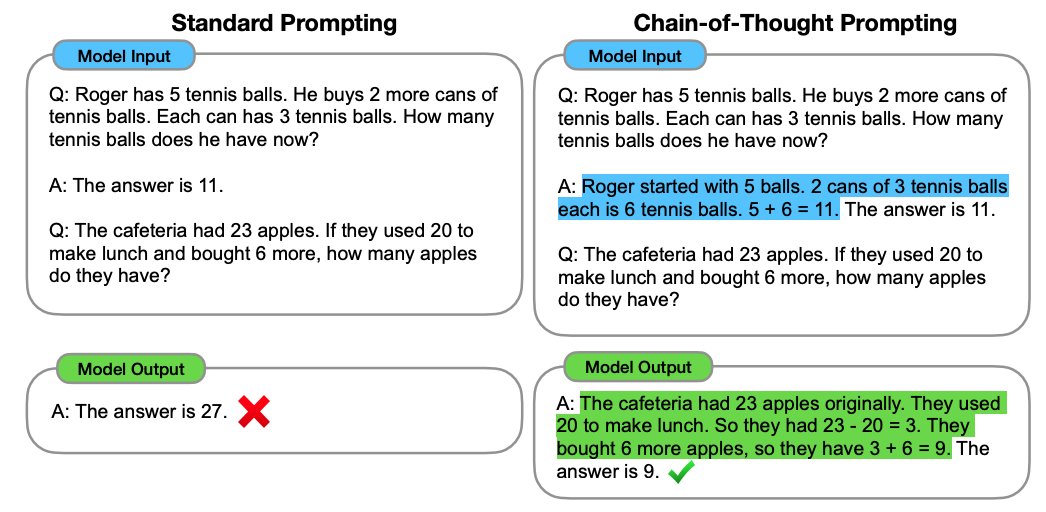

Chain of Thought (CoT) Prompting

Another approach for prompt engineering is chain of thought (CoT) prompting. Proposed by Wei et al., CoT enables complex reasoning capabilities through encouraging LLMs to explain their reasoning process. As depicted in Figure 15, involves providing the LLM with a natural language query and a chain of thought examplar. The chain of thought examplar is a sequence of steps that the LLM should follow to solve the problem.

Image source: Wei et al.

The main advantage of CoT prompting is that it makes the LLM’s reasoning process more transparent and interpretable. By explicitly providing the LLM with a chain of thought, we can see how it is arriving at its answers and identify any potential errors.

Another advantage of CoT prompting is that it can help LLMs to solve more complex and nuanced problems. By breaking down complex problems into smaller and more manageable steps, CoT prompting can make it easier for LLMs to solve them accurately.

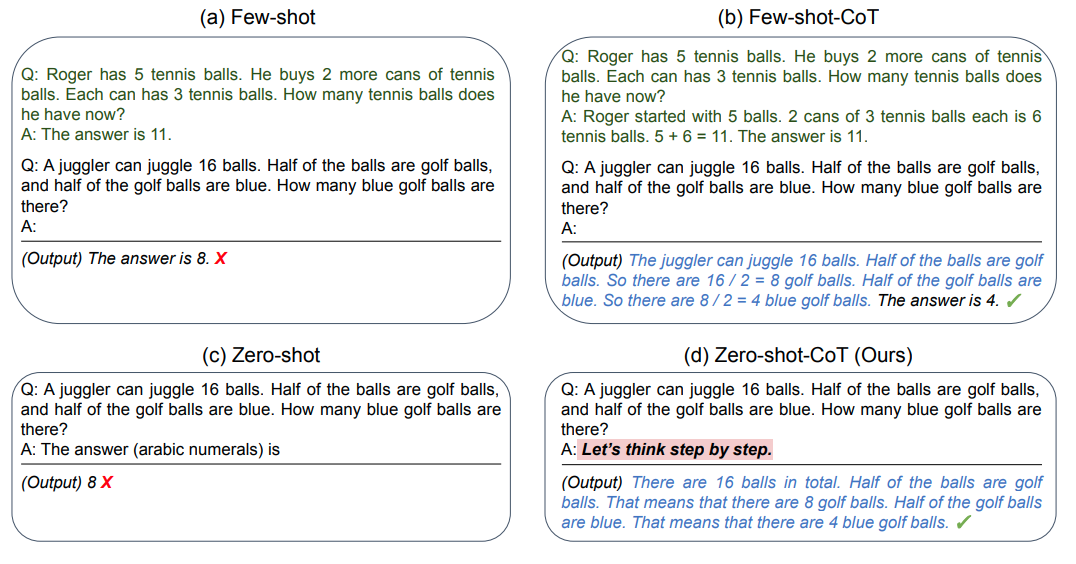

A recent development of CoT is zero-shot CoT Kojima et al., which involves adding the prefix “Let’s think step by step” to the original prompt without any explicit examplars (Figure 16).

Image source: Kojima et al.

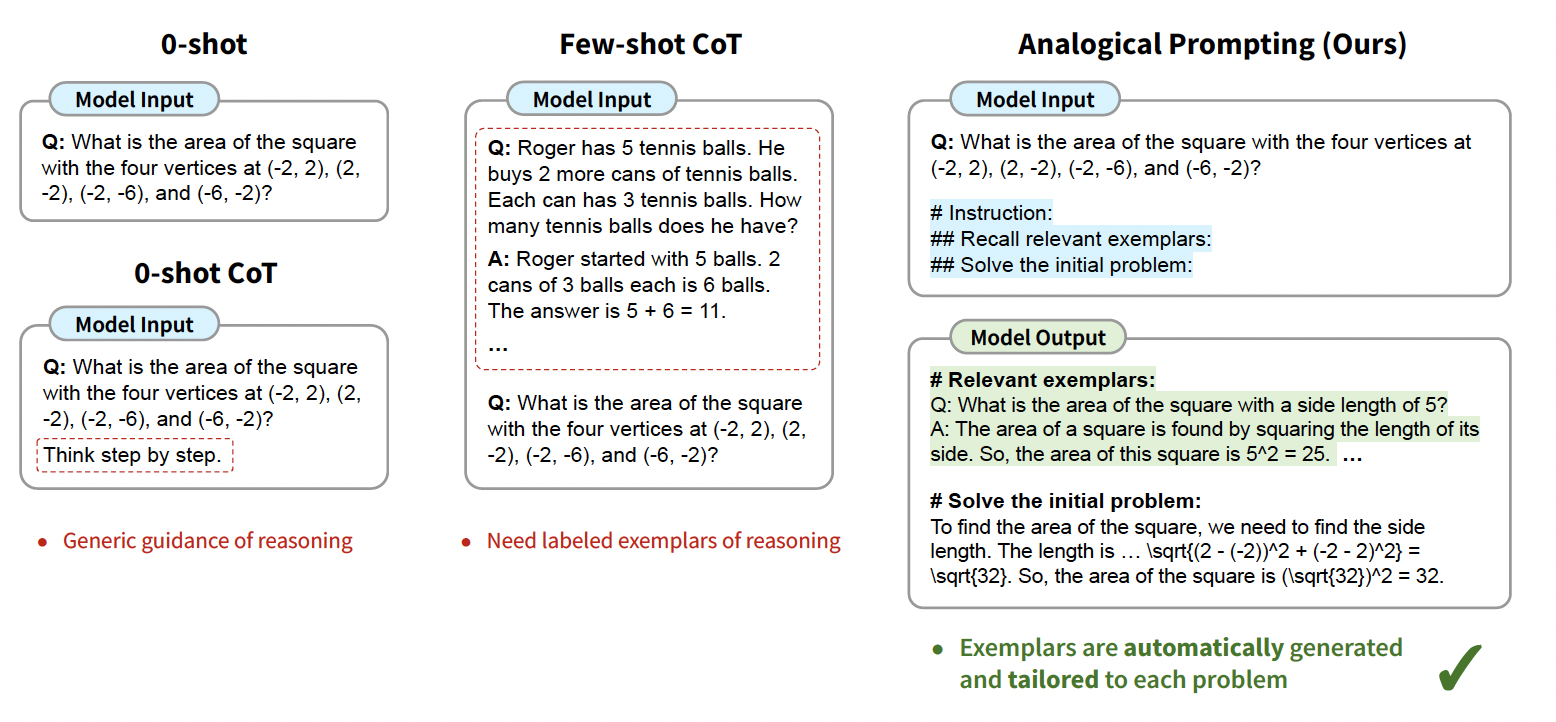

Analogical reasoning for CoT

Although CoT indicates impressive results on various NLP reasoning tasks, it requires providing relevant guidance or examplars and also manual labeling of examples. Considering these challenges Yasunaga et al. introduces a novel approach to automatically guide the reasoning process of large language models. The analogical CoT prompting makes LLMs self-generate relevant examplars or knowledge in context, before proceeding into solve problem (See Figure 17).

Image source: Yasunaga et al.

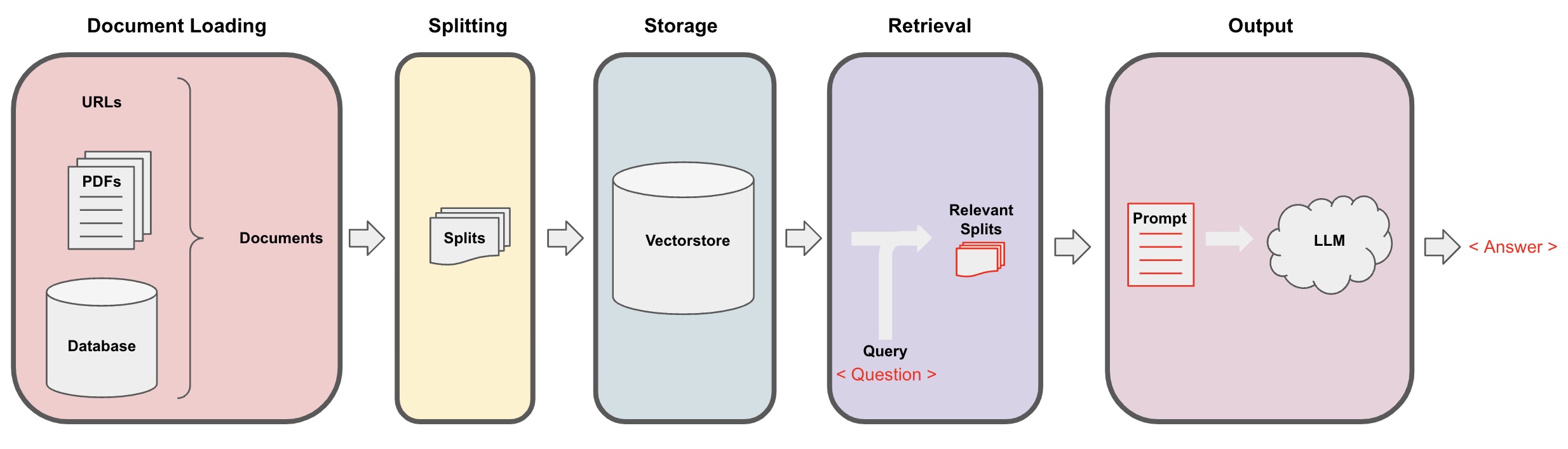

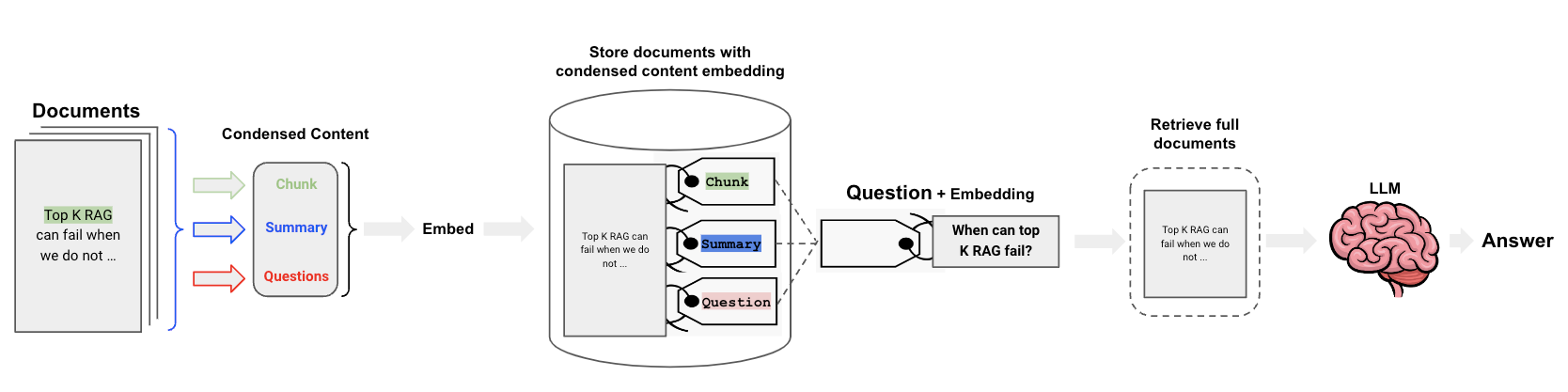

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

For straightforward tasks like classification, background knowledge is typically unnecessary. However, complex and domain-specific tasks require external knowledge. Meta AI’s Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) provides an alternative to fine-tuning LLMs with new external knowledge, which can be costly and time-consuming. RAG combines an information retrieval component (Facebook AI’s dense-passage retrieval) with a text generator (BART). The retriever first takes an input and retrieves relevant documents from a knowledge source (Wikipedia). These documents are included as context with the original prompt and processed by the text generator to produce the final output. This approach allows RAG to adapt effectively to changing information, addressing the limitations of static parametric knowledge in LLMs. RAG empowers language models to access the latest information without retraining, ensuring reliable output through retrieval-based generation. Figure 18 shows the pipeline for RAG:

- First we need to load our data.

- Text splitters break Documents into splits of specified size.

- Storage (e.g., often a vectorstore) will house and often embed the splits.

- The app retrieves splits from storage (e.g., often with similar embeddings to the input question).

- An LLM produces an answer using a prompt that includes the question and the retrieved data.

Image source: Langchain

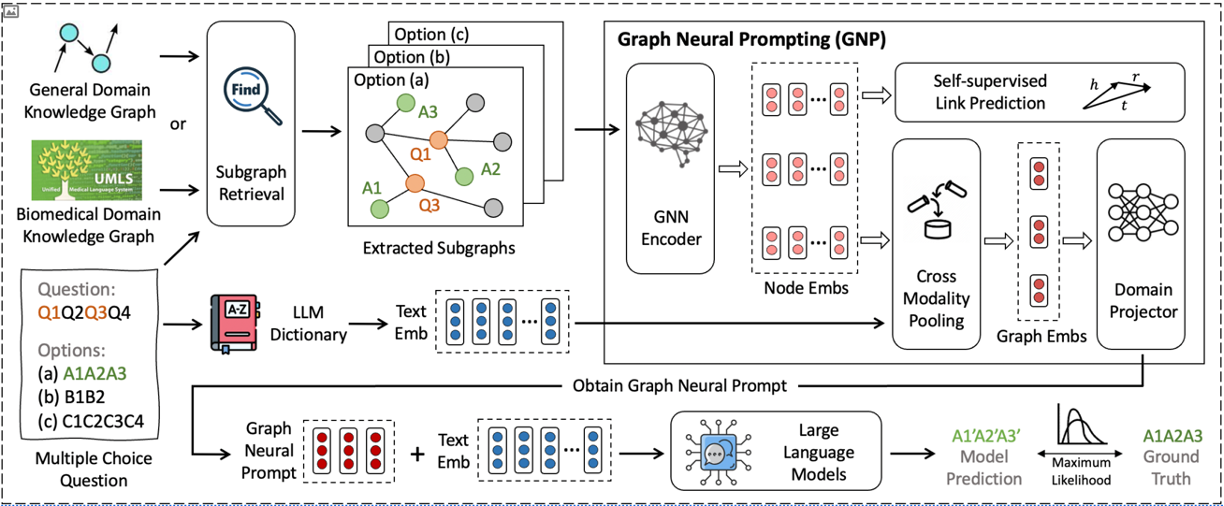

Graph Prompting

Knowledge Graphs (KGs), also offer a structured and systematic approach to knowledge representation. As a result, existing methods have emerged to apply KGs for injecting the knowledge into the prompt. In this context, Tian et al. introduced Graph Neural Prompting with LLMs (GNP) as a method to learn and extract the most valuable knowledge from KGs to enrich pre-trained LLMs (See Figure 19). The key contribution of this work is its ability to improve baseline LLM performance by 13.5% when the LLM is kept frozen. For more explanation of this framework check this post.

Image source: GN)

Liu, Pengfei, et al. “Pre-train, prompt, and predict: A systematic survey of prompting methods in natural language processing.” ACM Computing Surveys 55.9 (2023): 1-35. ↩

Brown, Tom, et al. “Language models are few-shot learners.” Advances in neural information processing systems 33 (2020): 1877-1901. ↩

Touvron, Hugo, et al. “Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288 (2023). ↩

Petroni, Fabio, et al. “Language models as knowledge bases?.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.01066 (2019). ↩ ↩2

Schick, Timo, and Hinrich Schütze. “Exploiting cloze questions for few shot text classification and natural language inference.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.07676 (2020). ↩

Schick, Timo, and Hinrich Schütze. “Few-shot text generation with natural language instructions.” Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. 2021. ↩ ↩2

Schick, Timo, and Hinrich Schütze. “It’s not just size that matters: Small language models are also few-shot learners.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.07118 (2020). ↩